The hearts of lost youth return to childhood… and also those of alleged adults

Luca Muglia. The invisible garden. Psychospiritual therapy for young people in difficulty (Il giardino invisibile. Terapia psicospirituale per giovani in difficoltà). Aliberti, Reggio Emilia, 2020.

Muglia bases his wide-ranging reflections upon his experience in the

recovery of young people in a Juvenile Criminal Institute in Southern

Italy. He advances in this book a proposal for the formation of the heart,

drawing on the sapiential knowledge of the Fathers of the Church and

Eastern spirituality, enriched with selected information from modern

psychology and behavioral sciences.

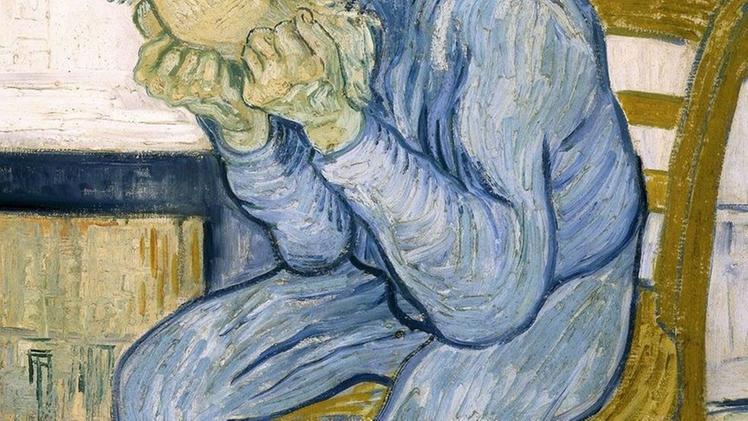

The “diseases of desire,” which grip lost youth (and even adults with

fragile personalities who have not matured enough), have multiplied in

postmodern societies, imbued with materialism and exacerbated

individualism. Muglia’s description of these pathologies in the first

chapter is extensive, even if sometimes it takes on “apocalyptic” tones.

The immoderate use of new technologies has exacerbated the problem of

personal identity formation, which has always been the challenge of every

generation. It is true that today it is more difficult to pass on a legacy

of “humanization” to the next generation…admitting that ours has acquired

it. “Human truths” (including moral, spiritual, and religious truths),

unlike technological and scientific progress, are not to be simply acquired

and put to work without commitment and personal risk. The “inner center” of

the person is at stake.

Muglia’s proposed therapy (which I would also call formation) aims

precisely at this spiritual core of the person, without the ploys

characteristic of cultural environments that have precluded – due to

ideological prejudice resulting from the Enlightenment – access to

“spiritual resources” present since ancient times in the tradition of

knowledge of every culture, including the Christian culture. The path that

Muglia traces in order to “educate the invisible” follows well-measured

steps: 1) the patience of becoming (which I would call educating about

realism); 2) the pedagogy of bold gestures, which I would call teaching to

make decisions, that is to form inner freedom, the only true freedom in

front of which the ability to choose between an offer of options more or

less varied is only a semblance; 3) all this with the help of the “inner

Master,” Someone who wants to work with us to get to be who we really are

and not one of the many identical moulds. Today, unfortunately, many young

people – and also not so young – act, operate… and become (therefore they

are) mimetic photocopies of standardized models created by the

“psychological engineers” of individual and social behavior who work at the

service of the god Money in all its idolatrous forms with which it is

dressed to entice one’s desires (power, recognition, sex, etc.). They are

false idols that cannot satisfy our desires, because they are just

effigies.

It is therefore, in my opinion, a daring, fascinating, and very useful book

for educators. Perhaps the author gets too carried away by an “academicist

itch” that leads him to fill the text with many scholarly quotations, which

sometimes take away linearity from his thought. The final goal, however, is

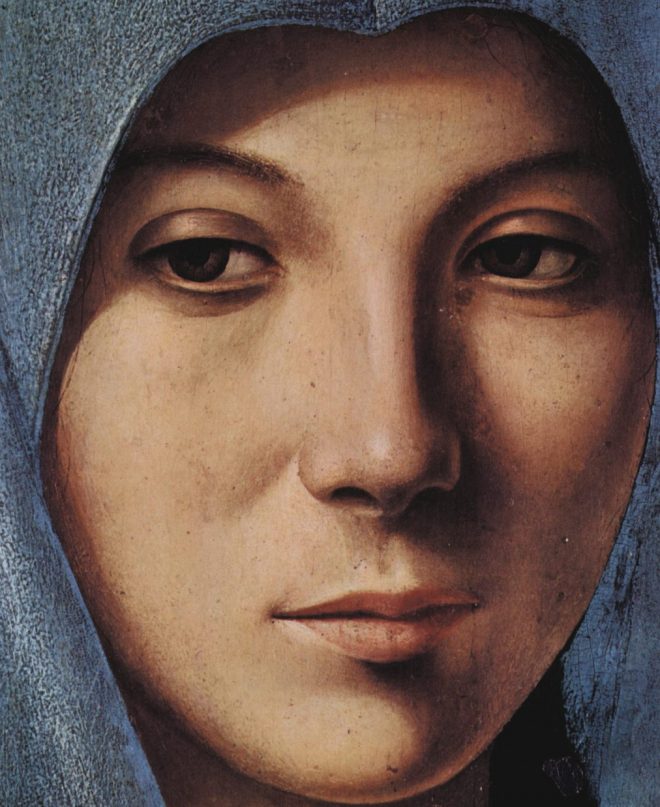

clear: to reach and purify the hearts of the lost or so-called “difficult”

young people.